Battle of Britain Hero visits Tongwynlais

Battle of Britain hero Dennis David’s father William Richard David, was born in Tongwynlais. The pilot fondly recalls in his autobiography his village visits to his beloved grandparents who owned the bootmakers. He also wrote of a visit back in the 1960s to his Aunt Beatrice, who took over his grandfather’s shop with her late husband Robert.

William David, his father, had left Tongwynlais for London to become an estate agent where he met and married Ruby Brocklehurst, a fashion model. William went to War in November 1915 and in 1918 Dennis was born in London. He was the first grandchild, ‘so mother had really achieved something for Wales, too!’ Dennis’s godfather was Oliver Locker-Lampson, a colourful character, who together with his father in the RNACD (Royal Navy Armoured Car Division) fought on the Eastern Front helping Russians flee from the Bolsheviks during the Revolution. David notes, ‘I can see now that much of what my father saw in Russia must have haunted him for the rest of his life.’ He recalls one of his father’s most treasured possessions was a white scarf given to him by a Russian woman he carried to safety. William was honoured with the Russian St. George Medal (4th class) and the Silver Brest Medal with St. Stanislas Ribbon for his bravery. After the war, his father’s way of coping with his experiences was to ‘go for drinks with friends.’ William was possibly suffering with what we call PTSD, and what they called ‘his sickness’. His father’s drinking, combined with rising debts, led to his parents divorcing when Dennis was eight. His mother decided that it was ‘for the best’ that they no longer have any contact with his father’s family.

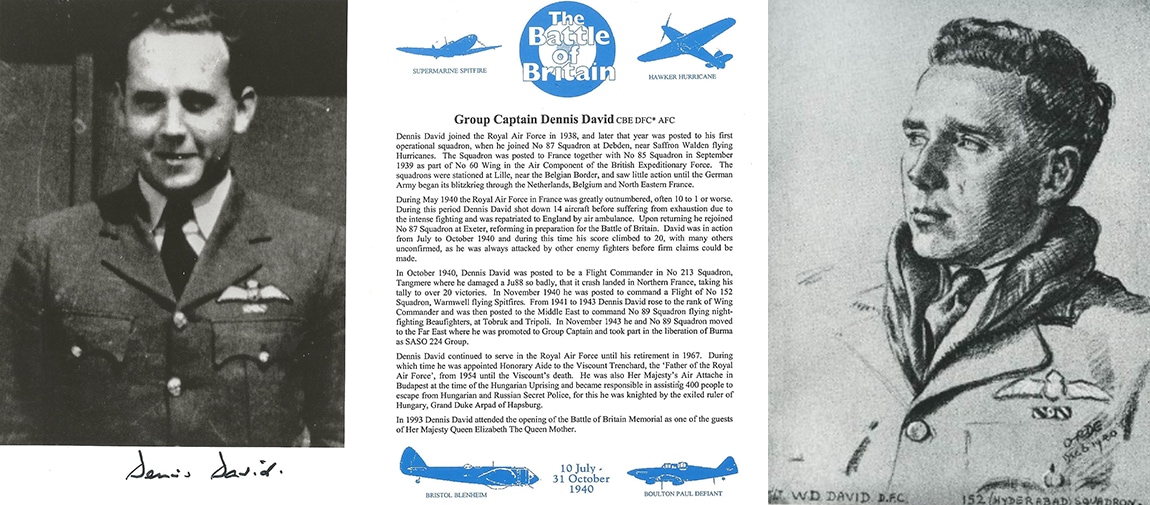

Group Captain Dennis ‘Hurricane’ David, CBE, DFC and Bar, AFC began his flying career in 1938 when he was posted to No 87 Squadron near Saffron Waldon. This particular squadron was equipped with Hawker Hurricane fighter planes. Deployed initially to France in 1939, Dennis recalls they had little action in what he described as the ‘phoney war’. This was until May 1940 when the Nazi’s began the Blitzkrieg in the Netherlands, Belgium and Northern France. Returning to Britain after being shot down and recovering from his injuries, the squadron were preparing for the Battle of Britain based in Exeter. It is said that Dennis was ‘continually in action’ from May to July 1940 shooting down over 20 enemy aircraft flying Hurricane’s and the infamous Spitfire. In 1941 he was posted to the Middle East night-fighting Beaufighters and in 1943 to Burma.

Dennis remained with the RAF until his retirement in 1967. Encouraged by his friends to write his memoirs and to right some literary wrongs, his autobiography Dennis ‘Hurricane’ David was first published in 2000.

He writes;

Because of a family rift in my childhood, I had not been back to my father’s family home in Tongwynlais near Cardiff since I was about seven. For all my globetrotting however Wales have somehow always exerted a pull, and I have the happiest early memories of times spent with my beloved Gran. So after retirement I felt I would like to return to my Welsh roots and possibly even pick up a few family threads. With what was undoubtedly going to be a very different new life lying ahead of me, this seemed a very good time to do it.

I feared the new motorway out of Cardiff might have swallowed up the little village, but to my delight I came upon a sign pointing to Tongwynlais, as the motorway swept on. I drove down into the village, and there was the church, and the little houses seemingly untouched by time. Surely that was the tiny shoe shop my grandfather owned? Now it seemed to be selling haberdashery, and other odds and ends useful to village life.

I parked the car and entered the shop a tiny lady, with her grey hair drawn discreetly back into a bun, came forward and asked if she could help me . I enquired if anyone by the name of David had lived there. She pulled herself up to her full height, which meant that she could just about look that me comfortably over the top of a high and very solid mahogany counter, and said, ‘I am Mrs Robert David’ in a lilting sing-song Welsh voice.

‘Aunt Beat!’, I exclaimed, ‘I’m Dennis’.

A lot of total displacement spread over her face, and then her eyes filled with tears, as she said, ‘Oh Dennis! How you’ve grown!’ It had been well over 40 years since I had seen her, when I was about seven years old.

The memories came flooding back, but I missed the smell of leather which had always permeated that little shop in my grandfather’s day. I used to spend hours there watching him make shoes and miners’ boots. Tongwynlais had been a mining village, and my lifelong respect and regard for coalminers were born of those days. It was a typical village community of that era. When a new baby was born, my grandfather would say, ‘Ah! Another pair of boots for the future’.

On bitter winter days, with snow on the ground, I used to see children running around with just little singlets and no trousers, for many families couldn’t afford them. The fathers could not pay for their boots outright, but would pay so many pence from their pay packet each week. On summer evenings, all the windows in the little street would be open, a Welsh voice would start to sing, and gradually the harmonies would be taken up by every household in the street. Welsh singing still brings a lump to my throat.

My grandmother, as I’ve only discovered in recent years, was not in fact Welsh at all, but born in Somerset. She was ‘Gran’ to the whole village, however. Everyone loved her, and she was a matriarchal figure. It speaks volumes for her that she was not only completely accepted as “village-bred” but was also well respected. She was never idle. With four big sons and two daughters to bring up, she could not spare a moment. She was only about 5ft 2in (157cm) herself, and used to say that when she could no longer do any work she would die. This is just what happened, for when she was too frail to see to her chores, she simply died.

She loved her family and her tiny home dearly. Every nook and cranny gleamed, the brass polished, the kitchen flagstones and the doorstep scrubbed. I have inherited the Welsh longcase clock, dating from 1736, which used to stand in the kitchen. It is just over 6ft tall (183cm), and I remember as a small boy standing by my grandfather, fascinated as I watched him wind it every day by simply pulling up the chain which had a 9lb (4.1kg) weight on it. Some years back I took it to an expert for an overhaul, and remarked on the rust on the chain. He touched it almost reverently, and told me it must never be cleaned, because it proved it was genuine.

‘I’m sure your old kitchen had a flagstone floor, did it not?’, he asked. He then explained that, as these old kitchen clocks have no enclosed base, the chain would inevitably have got splashed when the floor was washed. Hence the rust!

There was a great stir in the village when the Davids had the first flushing lavatory installed. It was in a special outhouse in the little back garden, and I remember the villagers calling round and, with due deference, asking if they might go out and see it, and perhaps be allowed to flush it. Some literally took a step back in amazement at this phenomenon, and it was generally agree ‘Ah yes, this is the future.’

Standing in that familiar little home once more, being warmly embraced by Auntie Beat and by one of my cousins who now lived with her, I found it hard to believe it was so many years since I had been there. I asked how the village had not been swallowed up by the motorway? Auntie Beat informed me with a triumphant smile that they made it too expensive for the authorities.

Aunt Beat was the last of the older generation. I bless the fact that I was able to see her quite a lot before she died some years later. I do not usually care for music at funerals, as I feel the occasion is too emotional for it to succeed purely as music. However, for Auntie Beat, the little church was packed, and with the first chord on the organ, the whole village seemed to harmonise just as I had remembered on those summer evenings. I didn’t want the service to end. Afterwards there was a gathering of the clans, for word had gone around the valley’s that ‘Dennis the pilot’ was coming, and relatives met up who had not seen each other for years. The sherry flowed, and one and all agreed that Aunt Beat had had a good send off.’

During 1940 Dennis was tasked with the precarious role of night fighter, looking out for enemy aircraft. Without radar, Dennis admits that it was an impossible task and a ‘complete waste of time’. However, he had been given the Cardiff and Bristol Channel area to patrol. He notes in his autobiography,

My childhood memories were vividly revived by the knowledge I was flying over Cardiff, my beloved grandmother’s home. On the spur of the moment one day I wrote her a short letter, saying we knew they were all having a very tough time, but that she must try not to worry too much, as I and some friends were flying over her at night, doing our best to look after Cardiff and to win the battle. I had not seen her since I was a child, but had always loved her dearly. Some years later a cousin of mine told me how Grandma had treasured that letter, and told one and all in the village, ‘Isn’t it wonderful to think of little Dennis flying around up there looking after us?’ Almost as if I had my own pair of wings! It apparently gave her immense comfort for the rest of the war, when in fact I was in the Western Desert or Burma. One never knows how such a spontaneous little letter like that can come to mean so much. I shall always regret that by the time I was in contact with the family again, she had died, so I never saw her again.

Further Research

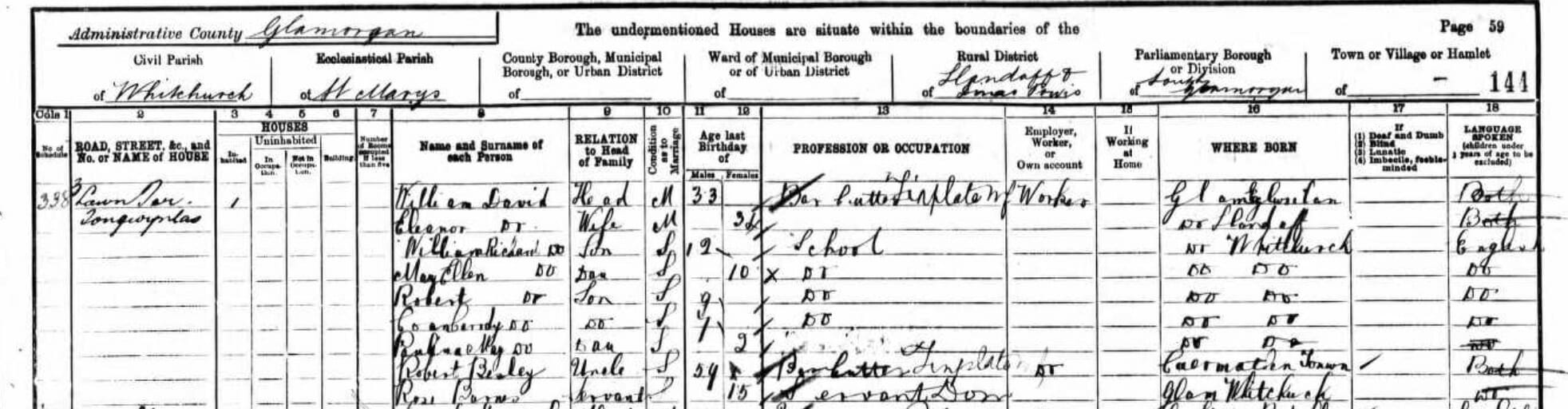

Looking through the 1911 Census it seems that the David family lived in Lawn Terrace which is now Merthyr Road. It shows that his grandfather William and grandmother Eleanor lived there with their 5 children including his dad William and Uncle Robert, another uncle and Rose their servant.

Who knows, one of them may even be in this photograph.

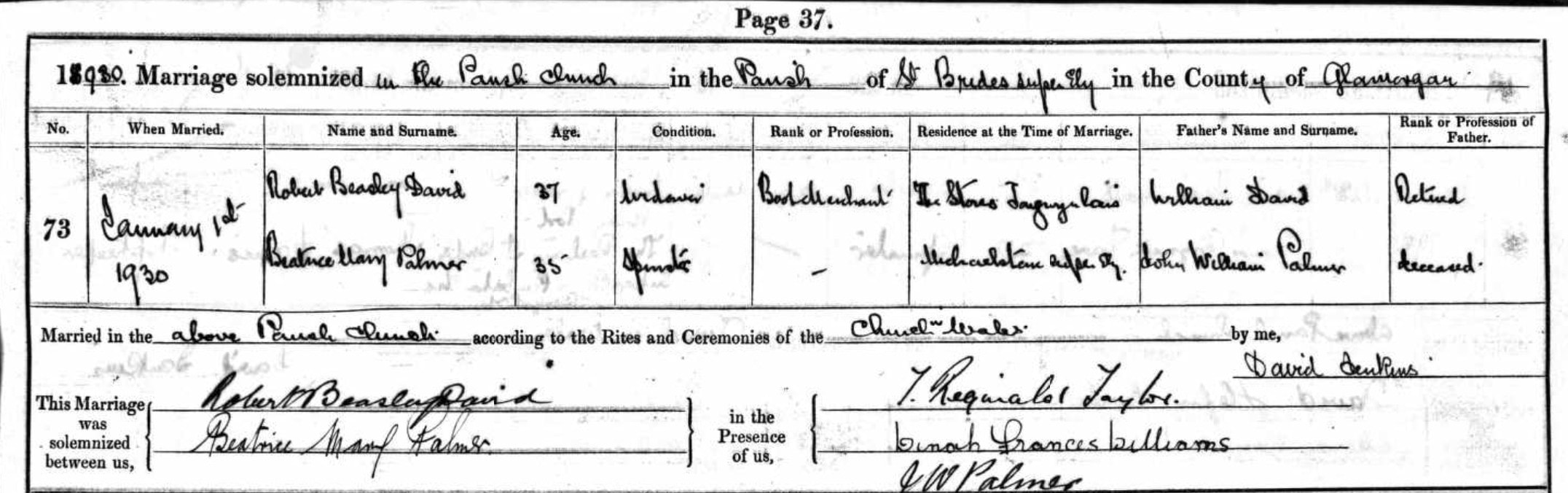

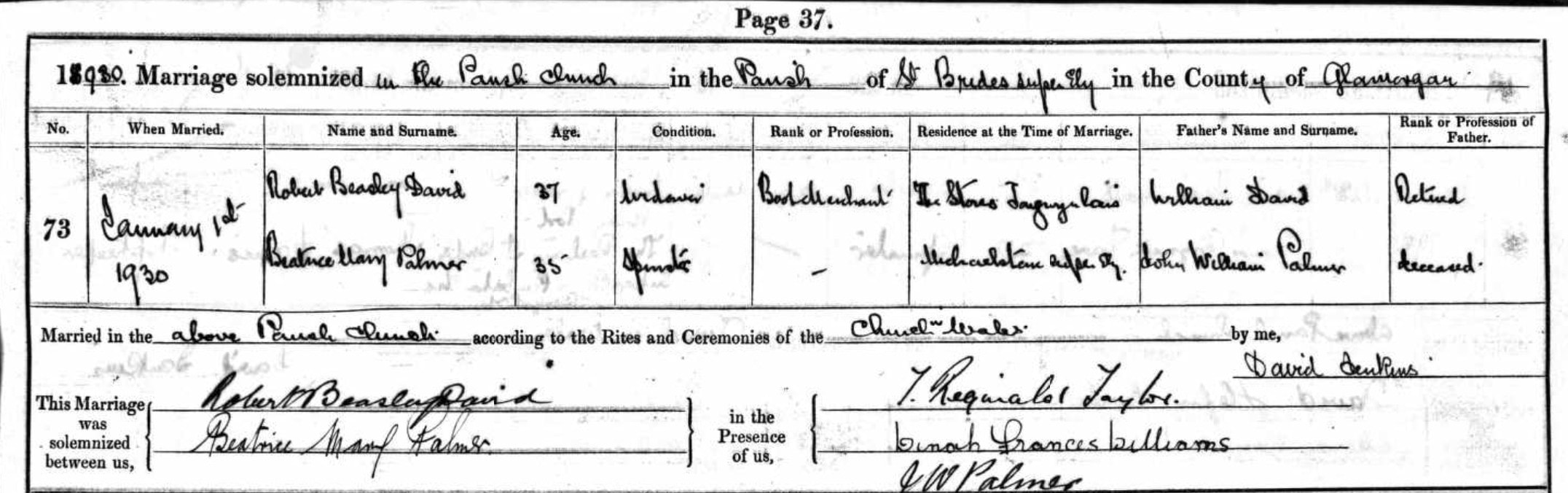

I also found the marriage certificate of Aunt Beat and Uncle Bob on January 1st 1930. Robert’s profession is listed as ‘bootmerchant’ in The Stores, Tongwynlais and his father as ‘retired’.

I also asked Val Bowden who has previously given us lots of information, if she had any recollection of Aunt Beat’s shop.