‘To Ton’ by Dic Mortimer

To Ton

On the hottest October day in Wales since records began (previous best 26.4°C, Rhuthun, 1985) I spent the afternoon in Tongwynlais at Cardiff’s northerly city limits. I hadn’t been there for over a year, so thought I’d better check it out to keep abreast of any changes.

In Tongwynlais the Law of Unintended Consequences has worked its contrary mischief to turn a place spawned on a communications super-highway into a place spurned on an inaccessible back-lane. The combination of geographical chance, changing technology and the human propensity to blunder has left Tongwynlais out on a limb, a flatlining dormitory where economic activity hinges on self-righteous lycra-sheathed cyclists tackling the Taff Trail and superannuated coach parties from Kettering shuffling round Castell Coch. But not so very long ago Tongwynlais was at the epicentre of Glamorgan life, the eye of a needle through which all human life passed.

TIP FOR READERS: If you can’t face ploughing through a rambling dissertation on transport systems in the Tongwynlais area, save yourself the effort and scroll down to the last three paragraphs for the downbeat pay-off line.

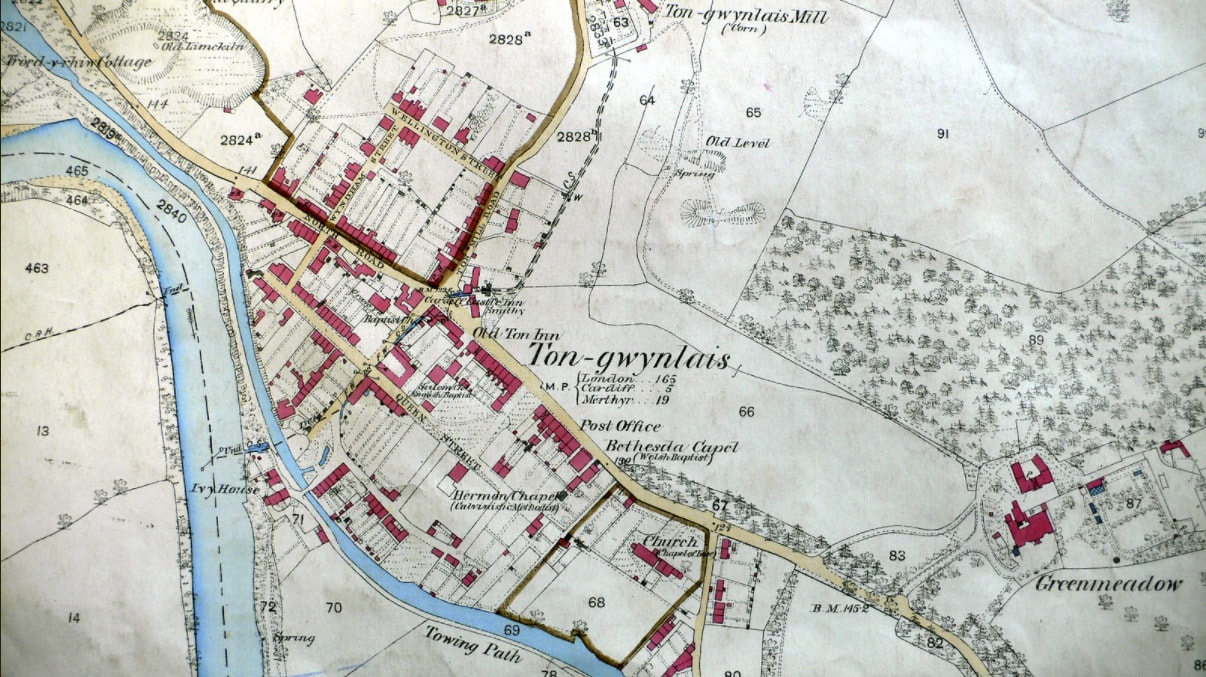

Tongwynlais sits at the mouth of the spectacular Taff Gorge, a narrow gap drilled by the river through the sandstone, shale and limestone chain of hills that form the final daunting obstacle on its journey from the Brecon Beacons to the Severn. A tiny hamlet of agricultural workers germinated where the Nant Gwynlais brook tumbled down from the beechwoods of Fforest Fawr to meet the Taff under an ancient Silures look-out post that would eventually become Castell Coch. And so it remained until the late 18th century, when the river valley was transformed to enable the easier movement of iron to the coast.

Two major projects, promoted by the ironmasters to link Merthyr and Cardiff, ran right through Tongwynlais and almost overnight turned the sleepy village into a bustling hub. First was the 1767 turnpike road, replacing the hill-top tracks over the Wenallt and Thornhill, bringing ribbon development of coaching inns and businesses to Tongwynlais, as well as one of the turnpike’s tollgates. Then in 1794 the Glamorganshire Canal was opened, hugely stimulating trade and industrial activity along its route. From the south the Canal entered Tongwynlais having curved around the steep, wooded Whitchurch escarpment to arrive in the village at Lock 41, getting closer to the Taff here than anywhere else on its 25 mile course – the steep drop from the towpath embankment down to the river claiming the life of many a boathorse over the years. Tongwynlais became the archetypal canal community, an important centre where the Canal company located its Boat Weighing Machine which calculated how much cargo each barge held. The Weighing Machine, one of only three ever constructed, would be dismantled in 1850 and moved to Lock 50 (Crockherbtown) before being moved again in 1894 to Lock 49 (North Road). After the Canal closed in the 1940s it was put on permanent exhibition at the National Waterways Museum on the Grand Union Canal in England, where it can still be seen today, a damning indictment of Cardiff’s disregard of its own industrial artefacts.

In 1815 the Pentyrch Ironworks ¾ mile upriver on the opposite bank (actually at Gwaelod-y-Garth, but within the Pentyrch parish) built a horse-worked tramroad between the Ironworks and the Melingriffith Tin Works downriver at Whitchurch. The Pentyrch & Melingriffith Railway (PMR) took a convoluted route from the quarries and coal-pits of the Garth and the Lesser Garth, ran parallel with the 1790 Pentyrch Feeder through the Ironworks down to Morganstown (then called Pentre Poeth – Hot Village), before cuttting across the valley and over the river into Tongwynlais at the Iron Bridge. At the time it was built this was the only bridge over the Taff in the eight miles between Llandaf and Trefforest. The Iron Bridge included a pedestrian walkway, so ending the ancient practice of crossing the river by stepping-stones and ferries, and drew yet more people through the Tongwynlais nerve centre (now there are 12 bridges along the same stretch of river including the Iron Bridge, which these days is a footbridge only and no longer made of iron – the original bridge was swept away in a flood in 1877 and this replacement, a favourite vantage point for photos of Castell Coch, was built of steel).

After crossing the Iron Bridge the Pentyrch & Melingriffith Railway’s main line followed the east bank of the Taff down to Melingriffith, but there was also a connection to the Glamorganshire Canal at Ton Lock via a branch tramline along Iron Bridge Road. At the Lock a small wharf was built where cargo could be unloaded from the trains and sent by barge down to the growing port at Cardiff, giving Tongwynlais another influential artery.

For 50 years the Canal was the main medium of transport, during which time coal took over from iron as the prime commodity. Tongwynlais had become a rich mix of agricultural and industrial workers surrounded by miles of beautiful countryside suddenly interrupted by the smoky pandemonium of furnace, quarry or pit. The rapid growth of the coal industry put an intolerable burden on the Canal, so to speed the transit of coal to the new Bute Dock the coal-owners constructed the Taff Vale Railway (TVR) in 1841, the first public railway in Wales and within 20 years the most profitable railway in the world. Thus another communications filament was squeezed through the Taff Gorge past Tongwynlais.

Engineered by Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806-1859) with his customary aplomb, the TVR’s original main line (it eventually had 23 branch lines) didn’t have a single tunnel despite running through mountainous country for most of its course. Brunel achieved this by the simple expedient of following the river virtually bend for bend. Entering the Gorge from the south on the river’s west bank under the Radyr escarpment, the TVR crossed the PMR near Cilynys Farm at a level crossing where a station called Pentyrch was opened, a testament to the importance of the nearby Ironworks. Being the senior line the PMR took precedence over the TVR for a while, but as the Ironworks faded and the coal traffic on the TVR increased it became clear that the arrangement made no sense and the station was in the wrong place. Following the opening of the Rhymney Railway (RR) in 1858, entering the Taff valley from the Rhymni valley through the Nantgarw gap to form a junction with the TVR north of Tongwynlais at Taff’s Well (originally called Walnut Tree Junction after the adjacent Walnut Tree Inn on the Merthyr Road), and then the Penarth Railway (PR) in 1859, running south from a junction with the TVR near Radyr Ford to the new docks at Penarth, it was decided to close Pentyrch station and replace it with stations at the two new junctions called Walnut Tree (now Taff’s Well) and Radyr, and at the same time the TVR was given precedence over the PMR at the level crossing.

Tongwynlais shook day and night to the endless rumble of coal wagons echoing off the Gorge cliffs, and as Cardiff hit its peak of coal-fired prosperity the juggernaut of development shifted up a gear and yet more railways slalomed past Ton. The Barry Railway (BR) of 1888 between Barry Docks and Pontypridd opened a branch line in 1901 from near St Fagans which ran north-east past Rhydlafr, curved around the west of Radyr and Morganstown, burrowed through the Lesser Garth in a 450m (1500ft) tunnel, vaulted across the Taff Gorge on a magnificent viaduct, skirted Fforest Fawr behind Tongwynlais and then headed up the Nantgarw valley to a junction with the RR at Caerffili. The Walnut Tree Viaduct, designed by James Szlumper (1834-1926), came to dominate the Gorge with its massive criss-cross lattice girders on six brick piers 35m (120ft) above the hurly-burly below, the catwalk under the track a dare-devil walk for generations of kids.

Then in 1909 came the Cardiff Railway (CR). It ran over the RRs 1864 direct line from Cardiff to Caerffili as far as Heath then turned due westwards in a shallow cutting, scoured a curving, deep cutting through Long Wood at Whitchurch, emerged from the forest at a sweeping diagonal bridge over the Canal at Lock 42 (Middle Lock) and, since all possible ways through the Taff Gorge had already been taken, was obliged to push through Tongwynlais on a high embankment, necessitating the demolition of a number of properties, before entering a 140m (450ft) tunnel under Fforest Fawr to get beyond the Gorge on the way to a junction with the TVR at Trefforest. Tongwynlais acquired its very own railway station on the elevated section of the CR to the south of the village and the extraordinary panoply of transportation routes shoe-horned into the Gorge was complete.

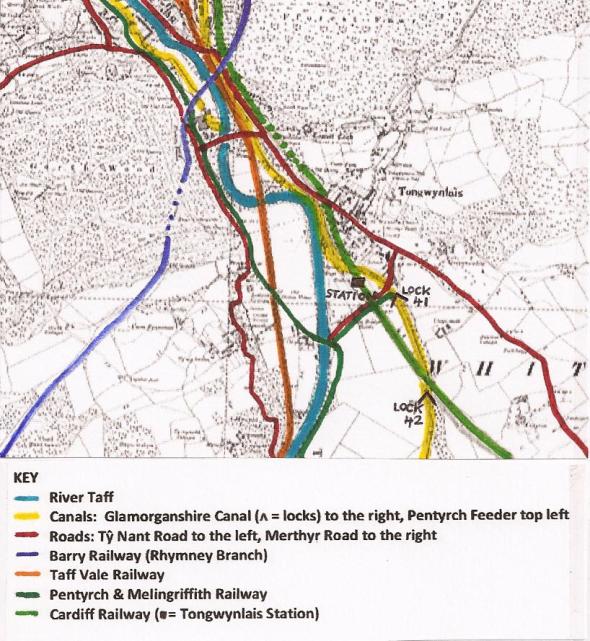

From west to east, the Barry Railway, the Radyr to Gwaelod-y-Garth road, the Pentyrch & Melingriffith Railway, the Pentyrch Feeder, the river Taff, the four tracks of the Taff Vale Railway/Rhymney Railway, the Glamorganshire Canal, the Merthyr Road and the Cardiff Railway jostled for elbow room in a mere 250m (800 ft) of width at the narrowest point. Cardiff was now reachable in 10 minutes from Tongwynlais. The coal Eldorado seemed endless. The 3rd Marquis of Bute (1847-1900) and his architect William Burges (1827-1881) had completed the conversion of Castell Coch into the castle of your dreams floating above the village. Tongwynlais had reached its apogee. This map of the Taff Gorge just before WW1 illustrates the position:

But bit by bit Tongwynlais was stripped of its relevance as Big Oil toppled King Coal in the 20th century, and one by one the engineering marvels of the Taff Gorge, painstakingly accrued by toil and sweat, were dismantled in an anarchic frenzy of gross ineptitude and crass wastefulness. The first railway casualty was the youngest of all the lines: the Cardiff Railway. The failure of this Bute estate project was a sign that the normally sure-footed Lords of Cardiff were losing their grip and falling prey to the fatal flaws that undermine all dynasties – arrogance, vanity and hubris. Their 150-year hegemony was coming to an end. I have written the full incredible story of Cardiff’s very own railway in Cardiff the Biography, so suffice to say here that this attempt by the Butes to rake in even more profit and strike a lethal blow against their old TVR foes by nicking their valuable Taff valley traffic was undone by crafty TVR machinations. TVR bosses bought a vital strip of land in Trefforest where the CR was supposed to converge with the TVR and so denied the CR the junction it needed to tap into the coal market. The most expensive five miles of railway ever built, an engineering tour-de-force requiring the diversion of the Taff at Nantgarw, 15 cuttings with colossal retaining walls, 15 overbridges and 12 underbridges – most at awkward angles, a tunnel, a skew viaduct and the culverting of countless streams, was taken over by the Great Western Railway (GWR) in 1922 and closed beyond Coryton by 1931. Tongwynlais lost its station after just 22 years – making it the shortest-lived passenger station (along with Glan-y-Llyn, Nantgarw, Upper Boat and Rhydfelin up the line) in Glamorgan history.

But that Law of Unintended Consequences I mentioned earlier can work in your favour, and for Tongwynlais the CR closure saved it from the fate that befell Coryton, Whitchurch, Rhiwbina and Birchgrove down the line. Their stations survived, attracted commuters and volume house-builders, and gave birth to the deadly-dull suburban sprawl of north Cardiff. Tongwynlais today is a much more rounded, friendly and unpretentious community of just 2,000 people – a small slice of the valleys in Cardiff. And, thanks to the Cardiff Railway, Cardiff can claim to be the only city to be topped and tailed by two red castles; their neo-gothic terracotta HQ of 1897 at the Pier Head a superb partner for Castell Coch peeping through the beech woods above Tongwynlais.

Surprisingly, the Pentyrch & Melingriffith lasted longer. Having been converted to a standard gauge locomotive railway in 1871 (when the branch to Ton Lock was closed), the quirky little freight line kept on chugging all the way through to 1961, supplying Melingriffith and carrying quarried stone. Its old riverside embankment between Forest Farm Road and Iron Bridge Road survives, along with evocative remnants of track, as an integral part of the Taff Trail; the Pentyrch station house, now a private dwelling, can also still be seen; and, following the conversion of the PMR between the Iron Bridge and Morganstown into a public footpath, the level crossing with the TVR is today a disconcerting pedestrian level crossing on the lush Taff water meadows.

Next to go was the Barry Railway, a part of nationalised British Rail since 1947 and closed by the UK Tory government’s slash’n’burn Beeching cuts in 1962 along with half of the entire Welsh rail network (including the Rhymney Railway lines north of Tongwynlais; the Penarth Railway lives on as part of the vital ‘City Line’ passenger service). Despite a passionate campaign to save it, the fantastic Walnut Tree viaduct was demolished in 1969 in an astonishingly philistine act of vandalism that eradicated an engineering pearl of international importance. The west abutment and two of the six piers remain, guarding the Gorge like enigmatic pillars of Hercules but barely noticed by drivers racing past on the A470, and the south portal of the BR’s Lesser Garth tunnel can also still be seen if you look hard enough. This compelling gateway into the maw of hell is a Grade A Cardiff nightmare that you enter at your own uninsurable risk. Don’t worry, I’ve experienced it so that you don’t have to. Use the search feature.

In the late 1930s a new arterial road from Whitchurch northwards by-passed the old Merthyr Road as far as the outskirts of Tongwynlais. Northern Avenue, aka Manor Way (after the housing estate at its southern end), aka the A470, signalled that the car era had arrived in Cardiff. And as one era began, another ended. The Glamorganshire Canal’s long decline into picturesque delapidation was made terminal in 1942 when, after heavy rain, the bank gave way at Nantgarw allowing three miles of water to escape. In the middle of WW2 no attempt was made to repair it and all movement of goods boats was discontinued. The remaining stretch of water between Treble Locks (nos 35-37) and the Sea Lock (52) was purchased by Cardiff council in 1943 and then progressively closed in stages by wilful neglect and short-termism. The Melingriffith to Tongwynais section kept its water as a nature reserve but that too got whittled away systematically. The Canal was entirely eliminated at Tongwynlais and all points north when the A470 dual-carriageway was extended up the Taff valley in 1971, utilising the Canal’s precise route so that scarcely a coping stone survives right up to Merthyr apart from a tiny but precious section in Pontypridd (see https://www.pontypriddcanalconservation.com/). More went when Long Wood Drive was constructed at the behest of Amersham International in 1977, and the building of the M4 and its Junction 32 in 1980 removed another chunk, leaving just today’s paltry ½ mile of water-bearing Canal at Fforest Farm, plus an evocative shallow depression filled with marsh plants between the M4 and Iron Bridge Road.

The construction of the A470 and the M4 sidelined Tongwynlais, incorporated into Cardiff in 1974, but brought no peace. Their junction happened to be right on Ton’s doorstep: ladies and gentlemen, let me introduce you to the star of the show…the Coryton Interchange! This stupendous triple-decker is the largest roundabout in the UK with a circumference of a mile, and is in many ways as impressive as the Walnut Tree viaduct. Complex engineering problems had to be solved to fit the junction into the tricky topography of contradictory planes and steep gradients, resulting in a giant concrete Celtic knot in which the A470 goes over the roundabout at one end and under it at the other while the M4 leapfrogs both on fat cylindrical struts. To try to manage the unmanageable flows in all directions, the Interchange has eight sets of traffic lights within its vortex of lane-switching bedlam. On a bad day, road works or any small incident at the wrong time can make journeys through the Taff Gorge slower today than the canal boats took 200 years ago. For Tongwynlais the shuddering low groan of traffic is incessant, no matter which way the wind blows, while access in and out of the village is either via a complete lap of the roundabout or a hair-raising scissors junction. An unexpected bonus though is the 12 hectare (30 acre) inner sanctum of the roundabout itself, reachable via a network of paths, subways and footbridges. Over 200 species of rampant plants, over-cooked by the micro-climate and gorging on a fine mist of exhaust particulates, battle for supremacy on the trucked-in soils of this gripping, deafening, self-contained island where the rabbit and the kestrel set the terms.

So, what did I do on my sun-baked afternoon in Tongwynlais? First, I noticed straight away that I missed a pub closure on recent Pubocalypse blog. Add the name of the Old Ton to the list. A rough and ready drinkers’ den, it dated back to the Merthyr Road itself and had seen off competition in Tongwynlais from the Bute Arms, the Cardiff Castle, the Castell Coch and the New Inn over the years. Now it’s boarded up and the ‘respectable’ Lewis Arms over the road is the last pub in Tongwynlais.

Then I was drawn like a magnet down Iron Bridge Road, under the A470 to the banks of the old Canal. Where it disappears into a black hole under the M4 I scrambled up the embankment above to survey the problems my long-gestasting ‘Bring Back the Glamorganshire Canal’ masterplan would have to overcome, alarming those motorists queueing bumper-to-bumper on the east-bound slip road who snatched a fleeting glimpse of a hook-nosed little slaphead with a notebook and pen thrashing through the undergrowth. Back down on Iron Bridge Road I took in 30 minutes or so of a South Wales Senior League Division 2 match (level 6 south of the Welsh football pyramid) between Tongwynlais and St Josephs (it ended 0-0). In the searing temperatures I drifted back towards the village and got an ice-cream in the Spar shop…and it was then that I remembered…I remembered Jamie.

Jamie Eade (1973-2010) was a Ton boy born and bred. He was a good pal. Lived near me in Roath for years. He loved music and movies and travel. When he quit his job with Admiral Insurance he used the money to wander the world far and wide, having great adventures in the Far East, Australia, the Pacific…but, in the end, he came back to Ton, to Pantygwynlais under the Greenmeadow Wood. In the end, he came home.