The buried treasure, the Ferret and the soldier of fortune.

Whilst this post title may seem a little ‘Mills and Boon’, the actual story is far, far more unbelievable. For me, it began last Sunday morning. I was searching for a snippet of a newspaper story I could add to the Facebook page for THS. ‘Castell Coch’ and ‘January’ were my filters. Up pops the following article in pole position;

HIDDEN TREASURE AT CASTELL COCH WOOD

THE PIRACY OF THE FERRET- A STRANGE NARRATIVE

A tale founded on fact, is a very common addition to the title pages of works of fiction, and, no doubt, many incidents in the ordinary life of an individual serve as a peg round which are woven a chain of events, more or less romantic in character, according to the skill or imagination of the writer. Probably the incidents which follow might, with a little expansion, form the chief episode in a three-volume novel of the modern school. It is not, however, intended to give any tinge of romance to this narrative, the facts connected with which have been long known to the writer, but they were given in confidence, and were consequently withheld until circumstances should arise which would render it no longer necessary that the confidence should be preserved. The circumstances at one time were peculiar, still there was nothing very unusual in the fear that they should be divulged, as at that time the knowledge of the incidents was confined to a few persons they were also surrounded with a good deal of mystery they were only revealed to the I few after considerable caution and it was apprehended that possibly he who divulged the secret might, from the vindictive character of some of the Spanish people who were concerned in it, become a marked man and find himself in I an awkward position. Whether there is any vast treasure hidden in some quiet spot within the precincts of the wood surrounding Castell Coch is not the province of the writer to prove, but to show that statements were made some time ago that such treasure was hidden there, that there were then many collateral circumstances to support those statements, and that lately other circumstances tend to show that there is a probability that they are true.

It was only some time after the first incidents were made known that the property deposited there was admitted to have been stolen, and when that was revealed, any further dealings with the parties by whom the statements were made ceased at once. With the first part of the narrative hundreds of persons, whose business engagements connect them with the docks, are perfectly familiar, and require little to bring up all the details to their remembrance, but this part is only, by an accidental circumstance, connected with the main issue. In October, 1880, an iron screw steamer, called the Ferret, entered the East Cardiff Dock. Her reputed owners were the Dingwall and Skye Railway Company, who had, it was said, chartered her to a gentleman in London, and he again sublet the contract to another. She was a steamer of considerable speed, and had been fitted up as a passenger vessel. Messrs Short and Dunn were the brokers, and she was soon loaded with a cargo of coal by Messrs Cory Brothers’ consigned to their agent at Marseilles. The captain was a gentleman who did not reside at one place during his stay at Cardiff, but for a part of the time lodged at the Cardiff Arms Hotel, or frequented it often. He spent money freely, and when the vessel left the docks, on the 23rd Oct, she had received on board an enormous quantity of provisions, and the steward’s cabin presented the appearance of a victualling apartment belonging to a gentleman’s yacht, and not the cook’s pantry for a cargo-carrying vessel.

There was a profuse supply of wine, spirits, and everything was of the best quality. There were certain things also about the vessel, which to the matter- of-fact people at the docks excited their suspicion that all was not right, and when the pilot, who took the vessel down channel, returned and spoke of the good cheer and the jolly life all were leading on board, that suspicion became strengthened. At this time there was staying at the Cardiff Arms Hotel, a gentleman said to be a Spaniard. He became acquainted with the captain of the Ferret, and when she left ostensibly for Marseilles, he sailed with her as a super-cargo. The Ferret never went to Marseilles, but landed her super-cargo at a small port on the south coast of Spain. Then at a distance from land she was repainted, her name altered two or three times, and the cargo was consumed as bunker coal. Her seizure by those on board became known to the owners. She was chased from one place to another, but was eventually captured and claimed for the owners in Australia by the proper authorities, the captain and crew were tried before a proper tribunal and sentenced to long terms of imprisonment for an act of piracy.

The circumstances connected with the chase and seizure of the Ferret gave rise to a good deal of interest at the docks. She was the subject of conversation for some months, but, like all similar circumstances, she ceased in time to be remembered. A long time afterwards a gentleman holding a distinguished position in the town, a borough magistrate, and also a man of considerable property, received a letter, purporting to have been written by a prisoner in one of the carceras, or prisons, at Madrid, asking, in some vague kind of way, whether the gentleman would assist in the recovery of treasure of some considerable amount deposited in a secret place near Cardiff. The letter was show to the head constable, who regarded it as a hoax. The stipendiary, to whom the letter also was shown, came to a different conclusion and eventually a reply was sent, which resulted in a correspondence being commenced, and maintained almost entirely on one side, but in the course of which a somewhat singular narrative was developed. The writer of the letters was a prisoner, but as everything in Spain was to be purchased, even indulgence to prisoners could be procured by means of bribery. The prisoner, after a time, admitted that he was at one time the private secretary of a Spanish nobleman who entrusted him with property to a considerable amount to be conveyed to England. He came to London with it, but from the first he evidently intended to appropriate the property to his own use. He left London, went to Bristol, and stayed for some time at an hotel there. He then came to Cardiff and stayed for a still longer period at the Cardiff Arms Hotel.

During his stay there his friends in Madrid informed him that his employer had discovered his duplicity, and agents were sent to England to arrest him. Fearing capture, he deposited the valuable treasure with which he had been entrusted in a secret place, not far from Cardiff, and then left in a steamer bound for Marseilles, but was landed on the coast of Spain. He was discovered by the agents of the nobleman, arrested, and tried at Madrid for feloniously disposing of property entrusted to him by his master, and sentenced to a long term of imprisonment in one of the Carceras in Madrid. To support this story official documents were enclosed, bearing the seal of the court, and duly signed by the proecutor. These documents stated the nature of the crime committed, which was that of misappropriating or stealing property entrusted to him, the name of the owner of the property, the person charged, which was the same as the writer of the letter, and the sentence passed upon him. The writer was anxious for an interview from the gentleman at Cardiff, to whom he sent the letter, at the Carcera, Madrid, when all details would be given.

In the later letters it was made known that the treasure had been deposited in the wood surrounding Castell Coch. A plan of the castle and wood was sent. A line was drawn from the Castle at a certain angle, and this, if continued for a certain distance, that distance to be given at the interview, would indicate the precise spot where the treasure was deposited. This plan was cut in two in a zigzag and herring-bone fashion the one half was retained, and on the gentleman presenting the other half to the prisoner’s agent at Madrid, whose name and address were given, the gentleman would receive the other half, and further information which would lead to the discovery of the treasure.

The letters were written partly in Spanish and English, but the details showed that the writer was acquainted with the Cardiff Arms Hotel, and also the direction to Castell Coch, Castell Coch itself, and the wood surrounding it. Several telegrams were sent, but as no reply to them was received at Madrid, the correspondence ceased, and the subject gradually faded from memory.

The time for which the man was imprisoned has expired, and a few weeks ago, three gentlemen, speaking English very imperfectly, were seen in the wood, and were also observed attentively looking at the Castle. In the summer time, when visitors are frequent, such a circumstance would not have excited any suspicion, but, during the winter months visitors are scarce, and strangers are almost certain to attract attention. They may have had no object but curiosity in view in examining the castle and traversing the wood in various directions, but it is possible there may be truth in the prisoner’s statements, and that these men are in some way connected with it. That such a crime was committed that such a man was tried and sentenced, the official documents of the court prove, and these, with the plan and letters, remain in the custody of gentleman in Cardiff, to whom they were sent.

(Cardiff Times 17th January 1885)

Now anyone who has received emails from an ousted African prince promising a portion of a fortune, will no doubt see a similarity in what the man received above. Who knew this practice had been going on for so long. Could the story be true? Is the treasure still buried? Who is the Spaniard? Can I afford a metal detector?

This is what I discovered…

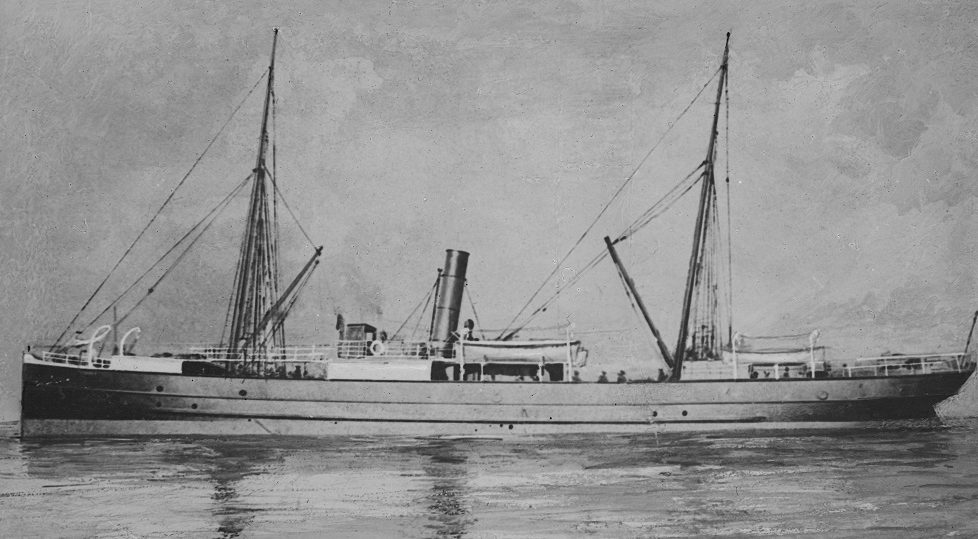

Was the SS Ferret a real ship? Yes. The SS Ferret was a cargo steamship and was built by J & G Thomson in Glasgow in 1871. She was 170 ft in length and able to carry 460 tonnes of cargo. Initially she was used as a ferry on the river Clyde. In 1879 the ship arrived at Steel & Co. shipyard in Greenock for essential maintenance. At the time of her disappearance in 1880, she was owned by the Highland Railway Co.

Was the ship stolen? Yes. A plot had been hatched in London, to steal the ship as a vendetta against underwriters Lloyd’s of London in protest at the company falsely charging the gang leader with forgery. To leverage the plan, the main protagonist operated a fraudulent ship merchants named Henderson & Co at 57 Grace-Church Street, London. There, they set about commissioning a chief engineer and uniforms, telling them that it was a cruise ship heading to Marseilles.

Initial consultations to the owners of the SS Ferret by phoney ship broker Joseph Walker, revealed that they would not allow her to be hired on general charter. However, they were tricked in allowing the ship to be chartered as a cruise for wealthy couple Mr. & Mrs. Smith, in order for the latter to convalesce in the warm Mediterranean. They sought references that were hastily forged and dispatched. Mr. Smith claimed he was a relative of the First Lord of the Admiralty W.H. Smith and a six-month lease was signed. In October 1880 the ship was re-fitted for its new cruising purpose. It was filled with provisions including £500 of quality wines, dry goods and silver plate, china, cutlery and crystal from local stores.

Of course, all the given names were false, and the first month’s payment and payments for the provisions were soon found to be fraudulent. It took some time but eventually after some frantic research, false references and unpaid cheques, the owners realised the ship had been stolen. Reporting it to the authorities, and subsequently the press, and the chase was on to find the SS Ferret.

Where did she sail? That October the ship headed to Cardiff with a running crew to fill her belly full of coal and pick up Mr. & Mrs. Smith and the commissioned crew. All additional crew signed ‘articles’ (employment contracts) in Cardiff on October 22nd 1880. Some at the Cardiff Coal Exchange.

On October 25th the ship left Cardiff for Milford Haven. Sailed from there on November 1st 1880 heading to Gibraltar arriving on November 11th. At this point the crew realised they were not heading for Marseilles after all. Sailing out of this port the ship’s crew were ordered to paint the funnel black and throw life jackets, empty casks, the SS Ferret plaque and any incriminating items overboard, giving the illusion the Ferret was lost. The ship was renamed SS Bantam, and the crew was warned to keep stum about the deception or the owner would, ‘blow their brains out’.

On 21st November the ship arrived in San Antonio, Cape de Verde taking on fowl, pigs and ‘necessaries’ in exchange for falsified bills worth nothing. The crew were all given slips of paper with their new names. Phoney ships articles were written using these alias’s and the crew’s signatures forged. The ship then sailed for Santos in Brazil arriving on 26th December 1880. They took on 3,992 bags of coffee, consigned to buyers in Marseilles, with no intention of ever delivering them. Instead, they headed to Cape Town on January 9th and weighed anchor on 29th January 1881.

During this voyage some of the coffee was used for fuel as coal supplies were running short. The ship’s name was changed again to the SS India, a red star painted on her funnel and the official paperwork forgeries commenced. The rest of the coffee was sold at this port for around £13,000. They left Cape Town on 14th February without the Captain who ‘went ashore and never came back’. The thought was that he may have got ‘gold fever’ and headed to Pretoria but some crew suggested there were arguments between him and the gang leaders. SS India arrived in Mauritius on 1st March for supplies and then onto Albany, Western Australia for coal and ballast, and finally on April 20th 1881 to Port Phillip, Victoria, Australia, where their journey ended.

Who was involved? Um, there was a reason I used few names in the timeline above. In a work of fiction, an author would describe the character by name, lists traits, associations and appearance. The reader could then easily follow the plot and storyline. In this non-fictitious story, the names and characters change so frequently, it is difficult to remember who is who and who was who and what was who and where was who and was who was. It seems in the 19th century you could change your name on a whim, and no one would be any the wiser. Very confusing.

Leader: alias George Boynton alias Mr Smith alias James Henderson alias Bolton

Wife: alias Mrs Smith alias Mrs Henderson (the Spanish beauty)

Captain: Thomas Watkins joined at Greenock left in Cape Town

1st Mate: Edward Rashleigh Carlyon alias Robert Wright alias Leigh

Pursor: Joseph Walker alias William Wallace alias Joe Wilson alias William Griffin

Steward: Henry Coffey joined at Greenock

2nd Steward: Joseph Brown joined at Cardiff

Carpenter: John Allen joined at Cardiff

1st engineer: William Griffin joined at Greenock

2nd engineer: Edward Blyth joined at Greenock (alias John Gray)

Fireman: Charles Davis Joined at Cardiff

Crew: Henry Coffey joined at Cardiff (alias Harry Martin)

Crew: Frederick Nicholas joined at Cardiff (alias Frederick Smith)

Crew: James Gray joined at Cardiff (alias James Smith)

Crew: John Wilson joined at Cardiff (alias Samuel Boyd)

Crew: Frank Pender joined at Cardiff

Crew: Matthew Robinson joined at Cardiff (alias Matthew Rowe)

Boatswain: Walter Rudd joined at Cardiff (alias William Jones)

What happened at Port Phillip? As I have said, the reports of the missing ship were of interest, not just to Lloyds of London, who insisted on peeled eyes in every port, but also the press who reported on the story all over the world. Queenscliff wharf Police Constable James Davidson, of Scottish descent, was on duty watching over the Bay. He was reportedly reading an article in the The Scotsman newspaper about the missing SS Ferret at the time, and noticed a distinct similarity to the reported description to the one sailing past. Once in port, the constable kept an eye on the crew and noticed there were a few discrepancies. With enough evidence, he reported the ship to his superiors and together with customs officials they seized the vessel. On board they found counterfeit stamps, seals, printing devices and everything a person needs to deceive officials. Crucially and incriminatingly they also found the paper evidence that confirmed it was the missing SS Ferret.

Who was convicted of the theft? The descriptions of the attempted escapes, capture, court lies, deceptions and shenanigans in this story, are something out of an Alexandre Dumas novel. For the purposes of this post, I won’t be going into these details but worth a read/laugh if you have time.

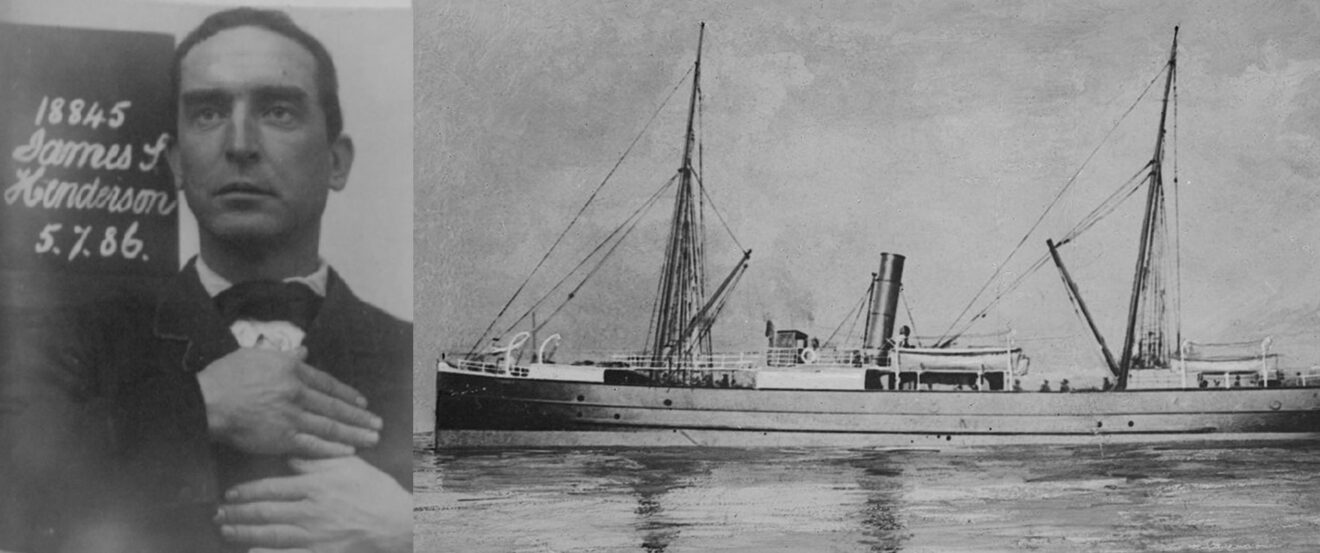

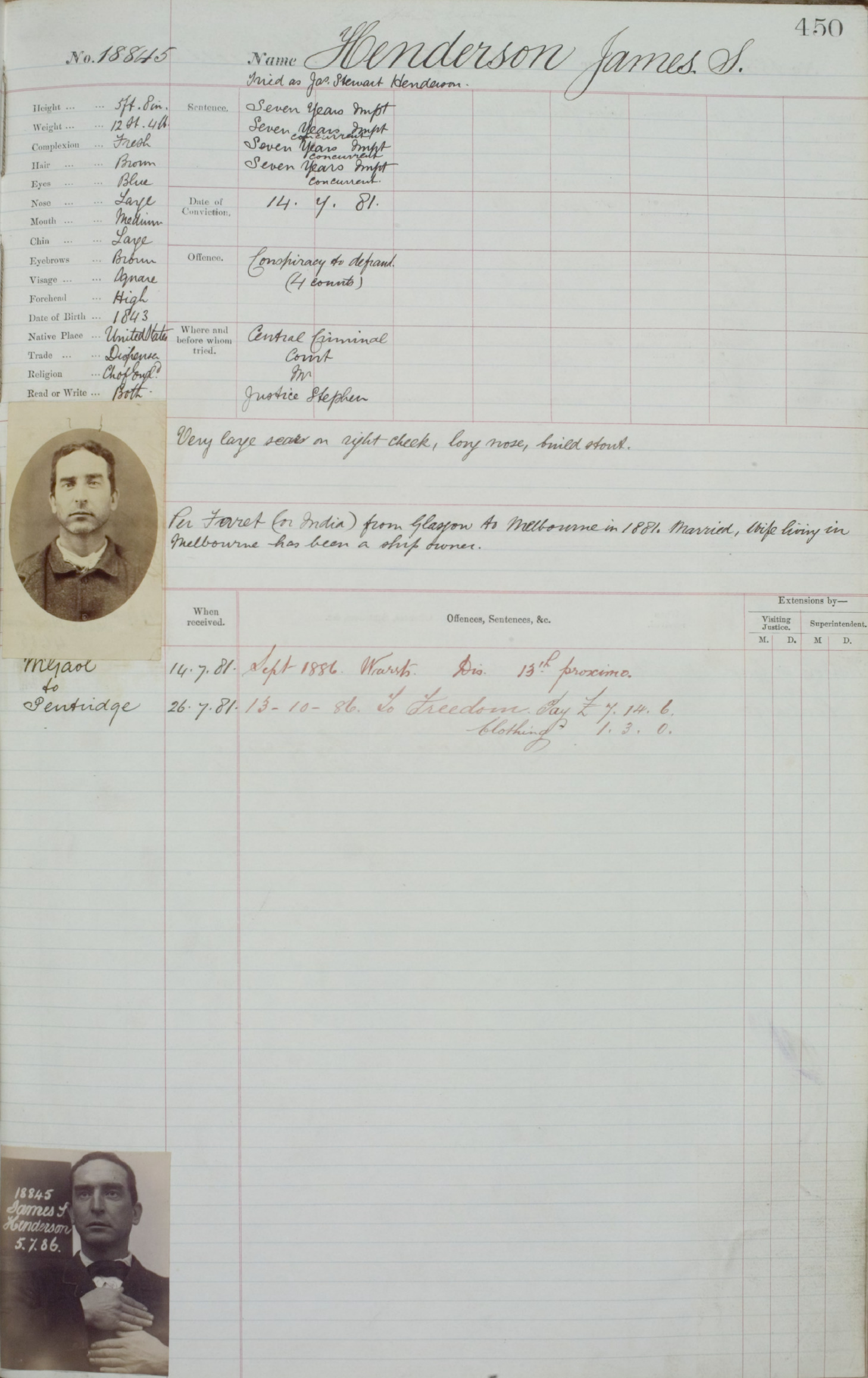

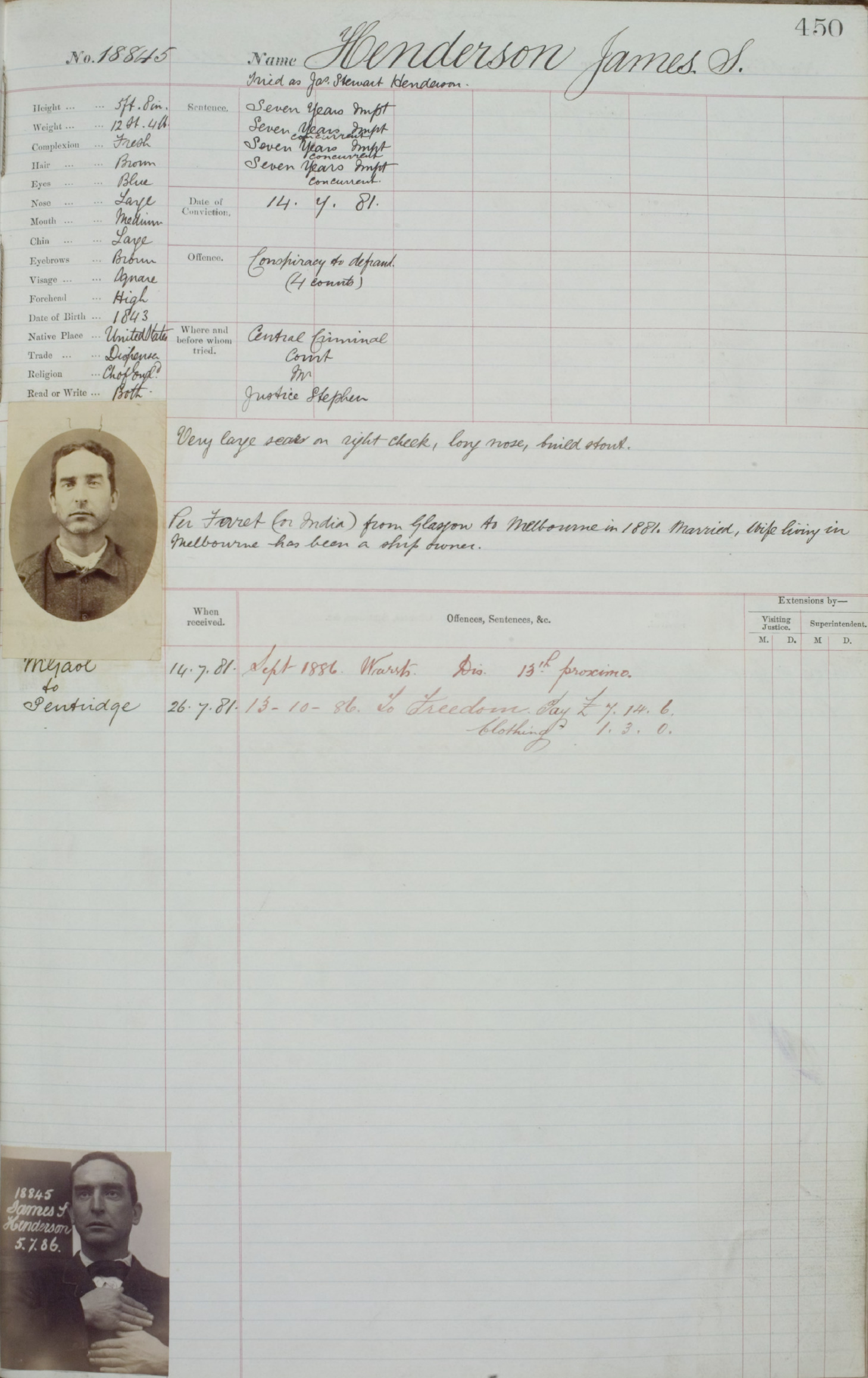

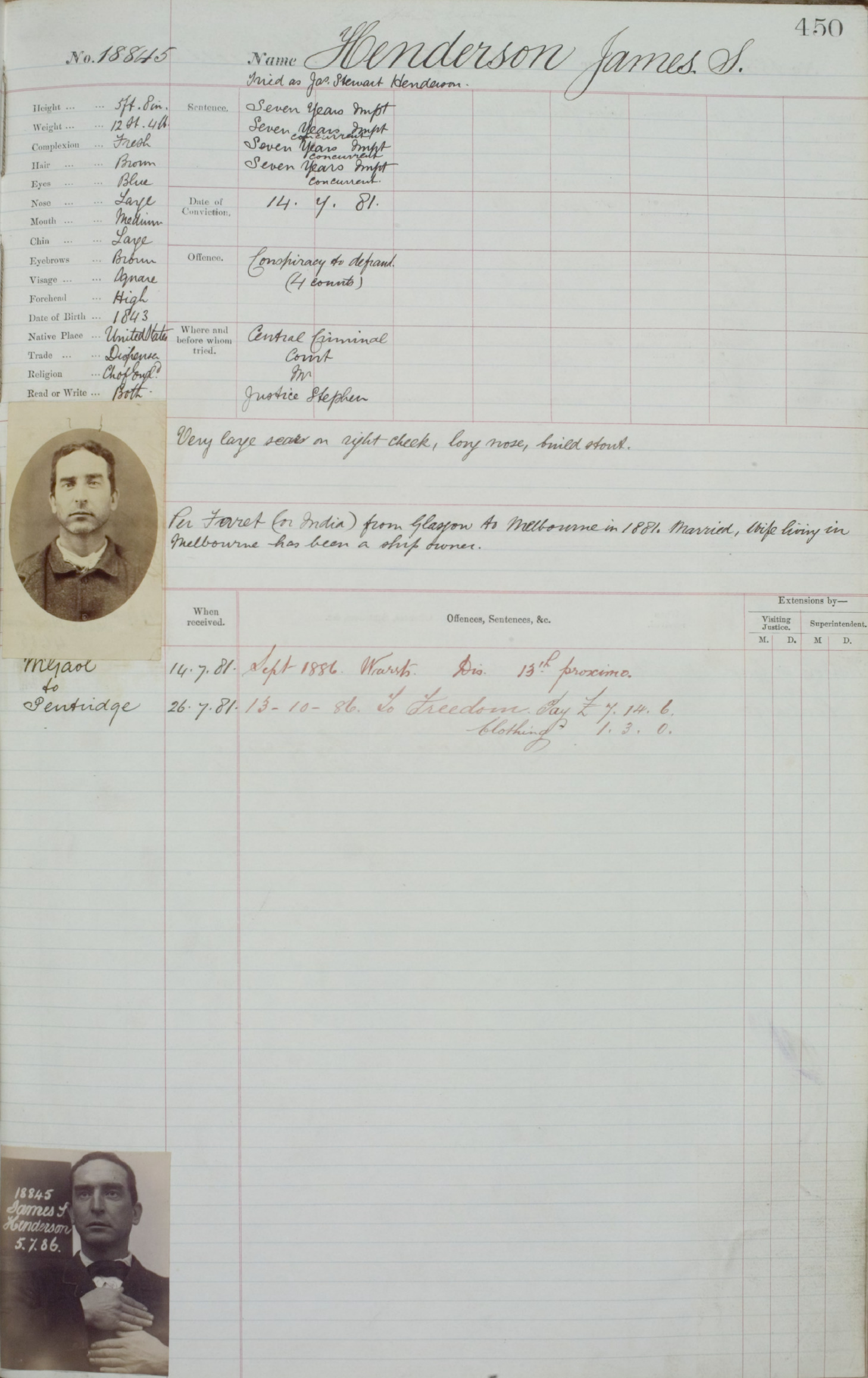

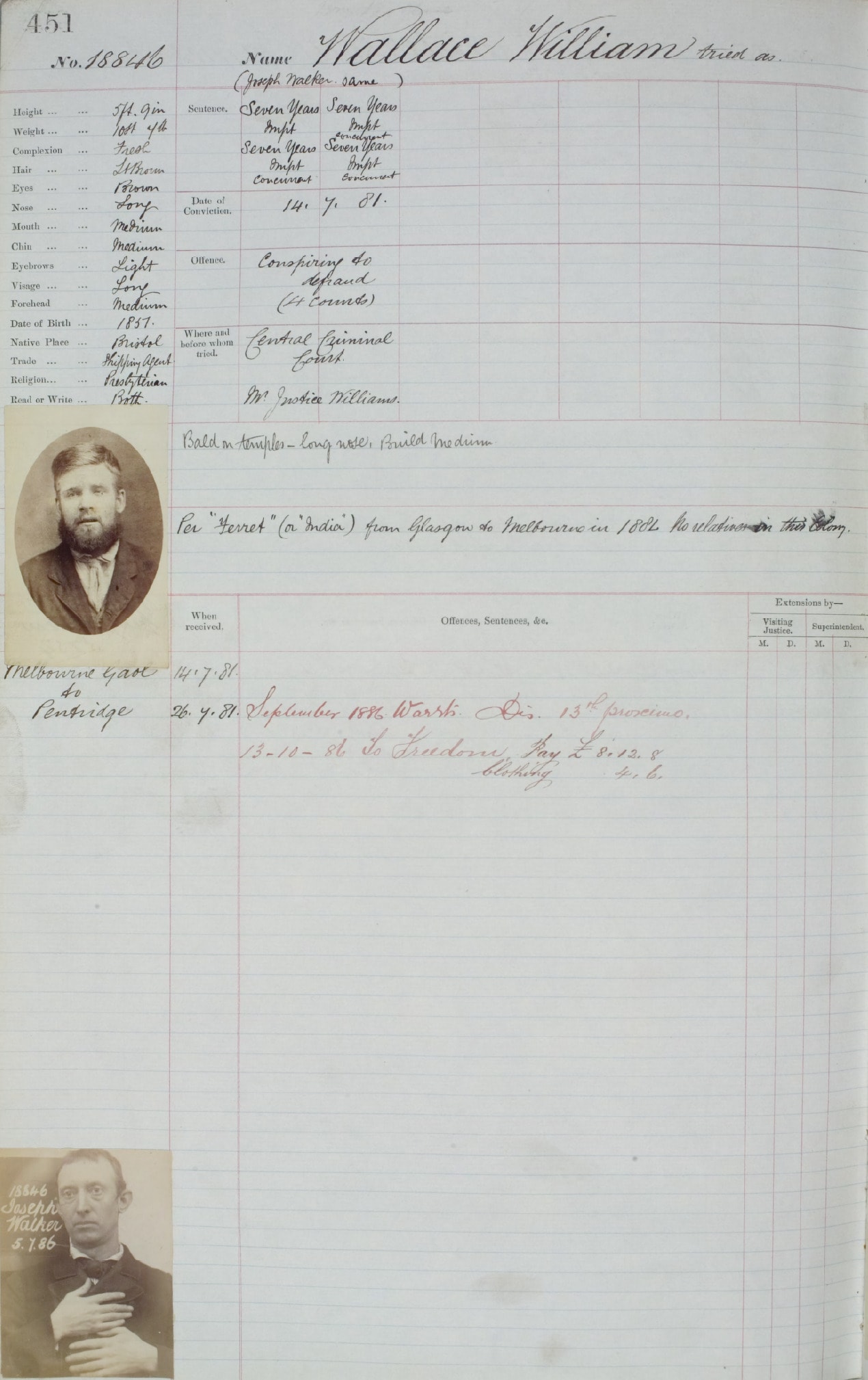

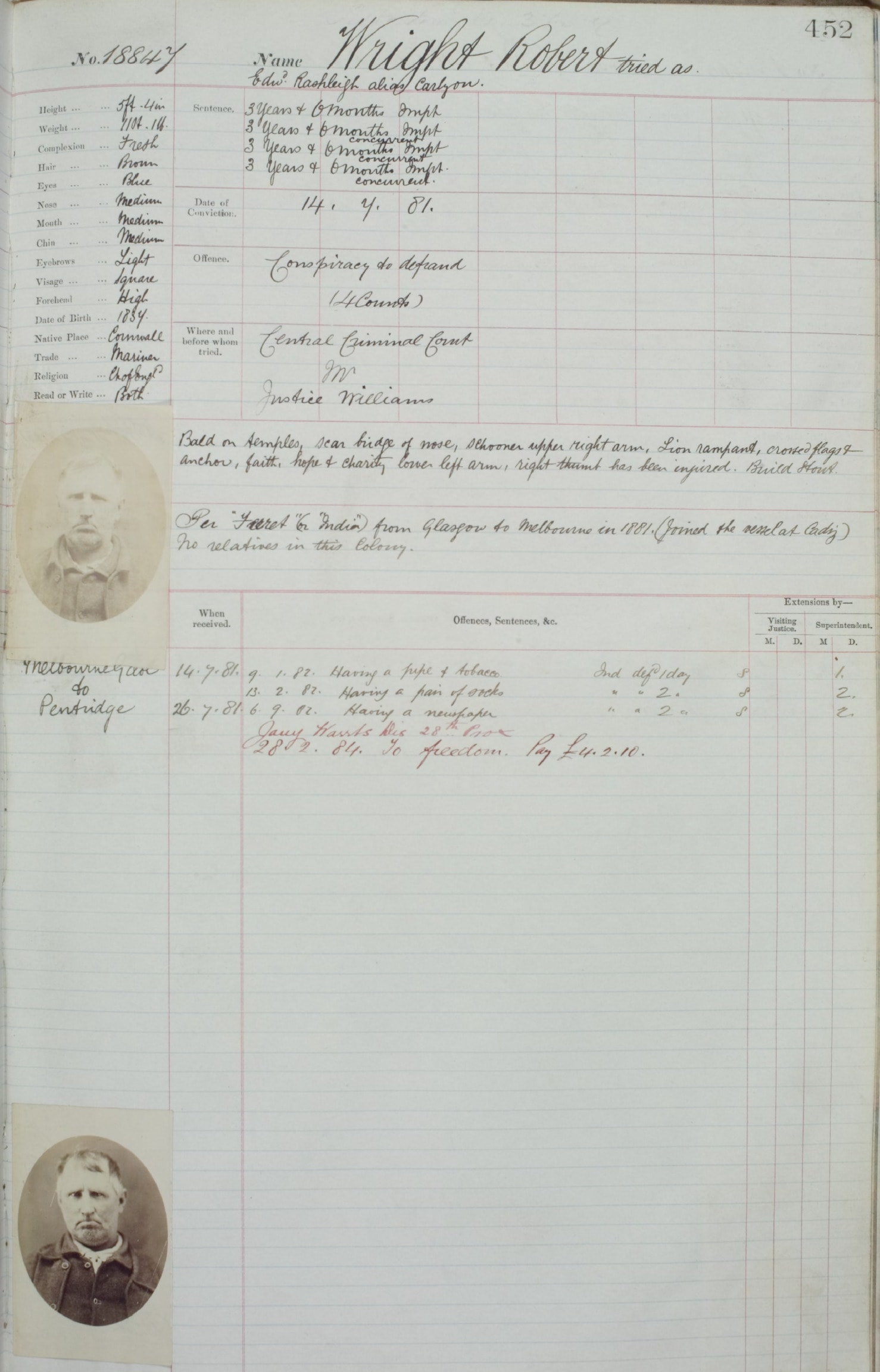

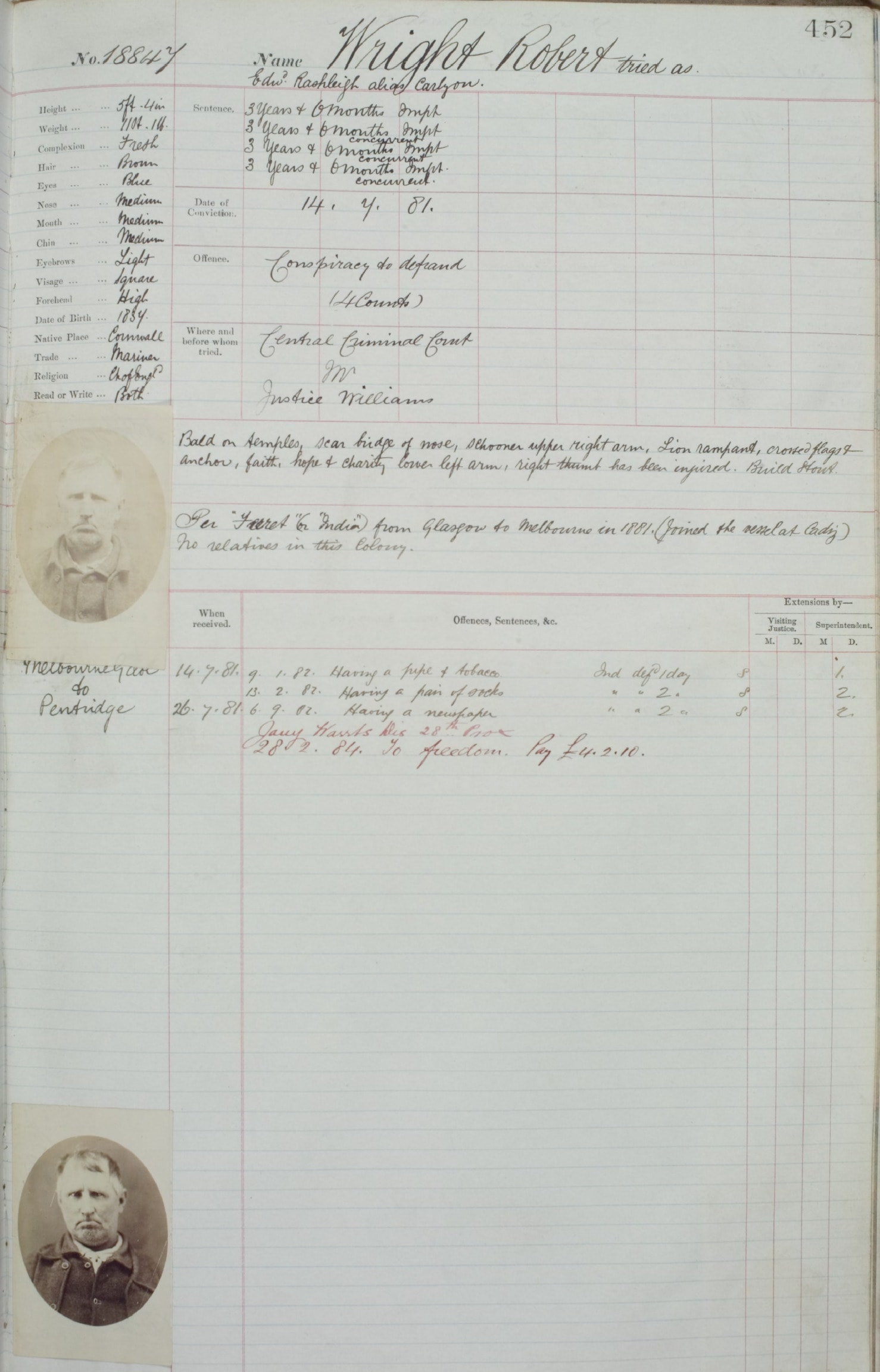

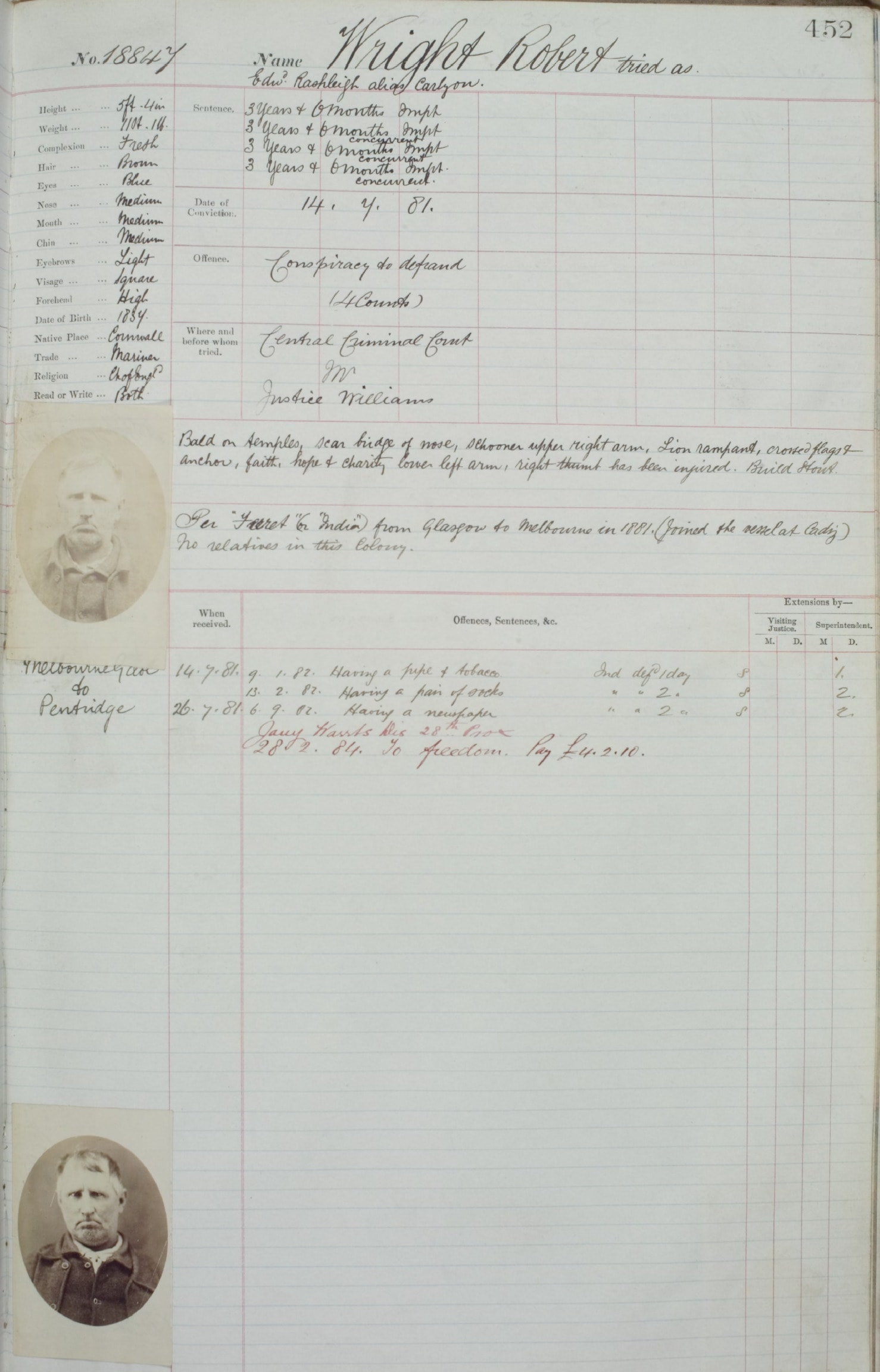

The three men below were tried and convicted for the theft of the SS Ferret. The rest of the crew were subpoenaed mostly to give evidence for the prosecution. Prisoner records below were sourced from the Public Record Office Victoria – Central Register of Male Prisoners

Leader: alias George Boynton alias Mr Smith alias James Henderson alias Bolton

Pursor: Joseph Walker alias William Wallace alias Joe Wilson

It seems the image on arrest is another much younger man. Walker is in the later image and matches the description.

1st Mate: Edward Rashleigh Carlyon alias Robert Wright alias Leigh

Who could have written the letter about the buried treasure? This is the most difficult question to answer. All three had links to London where the plot to steal the ship began. All three were in Cardiff at some point and could have buried the treasure. All three were in prison, although not in Madrid, at the time the gentleman in Cardiff received his correspondence. Joseph Walker alias William Wallace was a Bristol native and could be the letter writer. The ring leader Boynton (alias Henderson) notes his biography that he had buried items before, mostly guns. The India’s sister ship was called the Caceras and we already know the three were adept in counterfeiting stamps and seals. Could the Cardiff gentlemen have been duped into a Spanish deception when actually it was Australian prisoners? Did they tell of the treasure to fellow prisoners, who upon release, made a beeline for Castell Coch and the elusive treasure?

The dark horse of this melee, Mrs Henderson, was described in the local press as a ‘Spanish brunette beauty. A woman with large lustrous eyes, teeming with electricity and flashing at every glance. She was tall and dark, with a velvety olive skin and a magnificent set of teeth, as white as snow. Her placid gracefulness and swan-like dignity must be seen to be appreciated, as this sort of female is rarely seen.’ I also remember reading that her and Boynton (alias Henderson) stopped in a Bristol hotel before joining the ship in Cardiff. She was not convicted of any crime, so was free, and would have been party to all conversations and documents. After the others were convicted could she have gone behind their backs, knowing they were incarcerated for a few years. By the time they got out the treasure could be hers? In those days the presumption must have been that the letter was written by a man, but this woman, who spoke English and Spanish, has to be a suspect? Was she involved with a Spanish nobleman, stole his money and treasure and ran off with Boynton, changed her name to Mrs Smith, buried the treasure in the woods and set off on the stolen ship? The classic femme fatale often depicted in romantic novels … beautiful yet deadly.

Remember the Captain, Thomas Watkins, described as a person with dark skin. He left the ship in Cape Town and would have had access to the cabin where all the papers were kept. Did he depart because he found the treasure map and wanted to head back to dig it up, only to be arrested in Madrid? Did any of the disgruntled crew find a map and contact the gentlemen from their prison cells?

What about the all-American, filibuster, soldier of fortune and raconteur known as George B. Boynton aka Henderson, aka Smith aka possibly Jones too. He had the intellect, wherewithal, skills, money and the courage to write the letters and bribe the prison staff. After all, he did pull off stealing the SS Ferret. Did he look Spanish, possibly not, but what does Spanish look like? He was the master of deception and previously spent a lot of his time in Spanish waters, with Spanish crew, stealing Spanish things. He could have easily pulled off an accent and created yet another character and alias.

For my two pennies worth I’ll put my tuppence on Mrs Henderson, although I was originally convinced it was Boynton. Why? Because she fits the bill, had the freedom, the linguistics, the ability to lie and crucially the money.

Alas, I guess we will never know.

Could the treasure still be in Castell Coch Woods? If it was Boynton it is more likely to be guns rather than diamonds. If it were the Spanish beauty, surely coffins of gold. After all, the word ‘treasure’ means different things to different people. But, maybe, just maybe, whatever it is remains somewhere amongst the trees waiting to be discovered.

Now hand me the metal detector.

Oh wow! Thanks for posting this.

I occasionally write fiction based on local history. This one will be amazing if I ever get around to it. I’m studying again for the time being, but I’ll get to it at some point. It’s too good not to.

PS If you ever want anything on Green Meadow, I have a few things. Like I say, I collect this stuff to fictionalise it. I just don’t have time to join the THS right now because I’m going back to uni.

Hi Victoria,

Thank you so much for getting in touch! Boynton was certainly a character, if I had any talent I would write a screenplay about him. If you wanted to contribute anything you’ve written about the village please send it along. You will be fully credited for your work. Again thanks for getting in touch. Good luck at uni. Take care, Sarah