A childhood in Tongwynlais in the 1930s and 40s

My father Franklyn Brookman was born in 1926 and lived at 14 Railway Terrace, growing up in an era before the war when the Tongwynlais population was one thousand five hundred, unemployment was in the region of 60% and there were more chapels and churches (six) than there were car owners (four).

Home which he shared with parents Jack (John) and Minnie and older brother Oliver was a former lock keeper’s cottage. The Glamorganshire Canal at the bottom of the garden was still working at that time and he recalled that children would call out to the bargemen ‘what do you give your horse – Horlicks?’ as the lean beasts strained to pull their cargo. When clear, they swam in the canal and a short distance from the village school was a lock. Apparently, this enabled the brave (or foolhardy) to accumulate prestige amongst their peers by jumping the approximate nine feet span over the drop.

In his first year at the village primary, dad entered the scholarship, was lucky enough to pass and in time went to Caerphilly Grammar where he excelled at sport, representing the school at rugby and athletics. The journey to Caerphilly he recalled was via two antiquated Dennis buses, one for the girls and one for the boys. The two main drivers were ‘Bill the Fireman’ and ‘Offered Dum’, the latter so called because when talking about darts would say ‘we offered’um a one leg start’.

These elderly worthies, recruited because the younger men had gone to war, were full of spirit and if in close proximity to each other could be induced by the passengers to make the trip a race. Added excitement was provided by a level crossing, which when taken at speed would shoot everyone into the air.

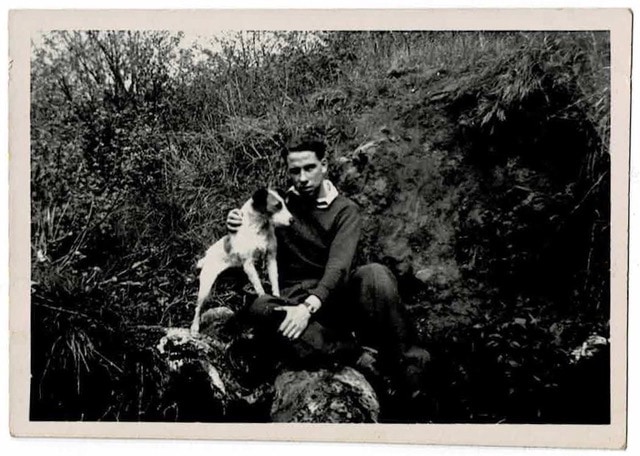

My father’s best friend was Frank (Nipper) Light. They would lug an old brass telescope up to an eyrie on Y Craig and look out at the shipping in the Bristol Channel. Their favourite spare time occupation however was poaching for rabbits. A number of dogs in the village used to lay about on street corners and dad told how they would set off with up to ten dogs.

The star was a dog called Monty who belonged to a local farm. Dad recalled how this dog could locate the boys wherever they were in some 36 square miles of wood and pasture and would come crashing through the bushes to greet them. Whilst in true poacher style they had acquired a shotgun, it was seldom used and their bag was secured with ferrets and nets.

At the advent of war, the boys joined the village Home Guard platoon which he remembered contained many venerable gentlemen. Based on their encyclopaedic knowledge of the local landscape, the boys were appointed guides to the platoon, a position which mostly enabled them to get back to the HQ first after a night deployment and sit in front of the roaring fire.

He remembered that one time a spigot mortar appeared in the guardroom to supplement their Lee Enfield rifles. Apparently, this equipment had a mind of its own and was usually sufficiently off target to make the operators cower for protection in a slit trench. Dad often thought that ‘Village Home Guard wiped out by friendly fire’ might well have made an unfortunate headline in the local press.

In early 1944, at the age of 17, dad volunteered for aircrew, but failed the eye test and then to his dismay on turning 18 was balloted and assigned to be a Bevin Boy down the pit. His appeal was turned down and dire consequences threatened – a situation made even worse by the fact that his friend Nipper had become a Marine Commando (112456 Marine F. B. Light) – so he reluctantly had no choice but to report to Penallta Colliery.

His time mining is the subject of another piece, but suffice to say his three years under the tutelage of one Harry Partridge working an often unstable ten foot seam with the coal pulled out by a horse called Quint, were formative years that he never forgot.

In spite of the poverty of the time, he looked back on his young years in the Ton as being an idyllic youth, and one which was rich in many respects. Good disciplined homes, excellent community relationships based on the chapel and what he came to appreciate as a headmaster in later life, a superb tripartite educational provision including plenty of technical and grammar school places.

Franklyn died in Norwich, Norfolk in 2006 and is survived by his wife Maureen and sons Gareth and Owen.

Article written by Frank’s son Gareth Brookman.

———————————————————————————————

If you would like to write an article about a Tongwynlais resident please get in touch we would love to hear their story. Thank you Gareth for sending us this wonderful article about your father.

First class. A fitting depiction of a great man and place; penned by a writer of equal merit.

Love you Dad,

Rich

Many thanks for sharing the story, hope to keep in touch. Gwyn

My mother who was born in queen street 1928 remembers the family her name was evelyn joyce ward

Wow what a brilliant piece of history so great to read and the photos are truly fantastic. Some of my late family lived in Railway Terrace but I can’t remember the door number they were Cyril David Stephens ( known as Uncle Dai) and his wife was Gwen they had a sone called Malcolm.